Context & Problem

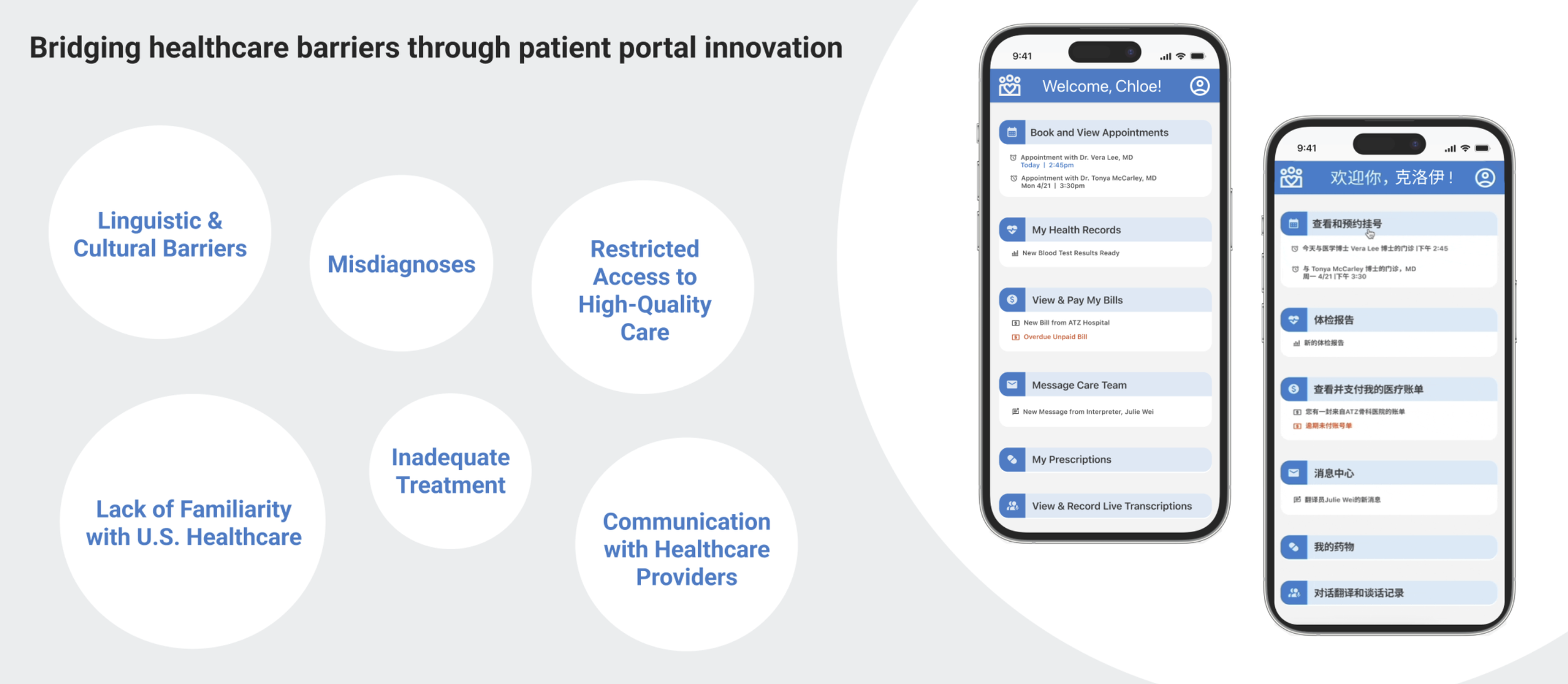

Non-native English speakers face systemic barriers in healthcare, where language gaps, cultural expectations, and family-mediated care often reduce clarity, trust, and patient autonomy.

Interpretation services are often fragmented, leading to miscommunication and poor retention of critical health information.

Many East Asian patients rely on family members to manage care, which can unintentionally limit independence and distort communication.

Despite available support systems, patients often struggle to fully understand, manage, and participate in their care—resulting in reduced autonomy and trust.

How might we design a patient portal that enables equitable access while preserving clarity, independence, and trust?

Executive Summary of Solution

The final solution is a universally accessible patient portal supporting patients and caregivers before, during, and after appointments. It is designed to increase autonomy, improve care understanding, and reduce caregiver burden.

- Language-Concordant Provider Search & Scheduling

- Family & Caregiver Management

- Live Transcription & Post-Visit Access

My Role

+ Designer

Chloe Minieri

Co-Lead · Research & Design

I co-led the project from research framing through prototype validation, ensuring every design decision was grounded in user needs—particularly for marginalized communities with limited English proficiency.

Project Team

Research Strategy

We began by aligning on what responsible design meant for a population often overlooked in health-tech.

Rather than validating a solution, we sought to understand where language, culture, and family dynamics disrupt care experiences.

Research was structured in phases—moving from systemic insight to deeply personal, lived experiences.

Research Methods

Text Mining

Surface unfiltered pain pointsAnalyzed online forums and community discussions to understand the language, frustrations, and mental models of patients and caregivers—insights often softened or omitted in interviews due to social desirability bias.

Participatory Journey Mapping

Identify breakdowns across the care journeyFacilitated workshops where patients and caregivers co-created their healthcare journeys, from symptom awareness to post-visit follow-up, highlighting moments of confusion, stress, and reliance on others.

User Interviews (Purposive Snowball Sampling)

Capture diverse lived experiencesConducted semi-structured interviews with 10 patients and caregivers to explore challenges in healthcare comprehension, cultural and language barriers, and differences between culturally concordant and discordant care.

Thematic Coding

Translate research into design criteriaSynthesized interview transcripts and workshop artifacts using inductive and deductive coding to uncover recurring patterns and inform prioritized design requirements.

Research Findings

Synthesis across research methods revealed four core themes that informed our design priorities.

| Theme | Observation | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Information Overload | Patients struggled to recall diagnoses, instructions, and next steps after visits. | Poor recall reduces adherence and increases dependence on caregivers. |

| Cultural Discordance | Cultural misalignment reduced trust and willingness to ask questions. | Low trust limits engagement and care quality. |

| Caregiver Mediation | Family members frequently acted as interpreters and decision mediators. | This undermines patient autonomy and burdens caregivers. |

| Access Limitations | Existing portals lacked multilingual support and clear navigation. | Limited access reinforces inequitable care experiences. |

Design Process

Impact-Feasibility Prioritization Matrix

Prioritize design focus areasWe translated insights into “How Might We” statements and plotted them on an impact-feasibility matrix to prioritize the features most likely to improve care experience efficiently.

Crazy 8s & Proof of Concept

Rapid ideation and validationThe team generated multiple concepts through Crazy 8 sketching exercises. Key ideas were consolidated into proof-of-concept flows, which were validated with 5 target users to test clarity, usability, and effectiveness.

Designing & Iterating the Application

Designing the Application

Information architecture & core flowsWe created information architecture and wireframes for core flows, including:

- Booking appointments

- Selecting language-concordant providers

- Family account management

- Live transcription during visits

- Post-appointment follow-up

Iteration

Usability testing & refinementsConducted multiple rounds of usability testing and refined the portal based on frequency-weighted feedback. Key improvements included:

- Simplified family management controls

- Improved labeling for transcription features

- Enhanced clarity in appointment booking and follow-up screens

Research Ethics & Inclusion

Because our participants are often excluded from health-tech research, we treated language access as an ethical requirement—not a convenience. All research and prototype materials were translated into participants’ target languages, with usability testing conducted using a fully translated Chinese prototype.

We also accommodated varying levels of digital literacy by supporting participants with remote setup when needed, ensuring everyone could participate comfortably and confidently.

Final Prototype & Outcomes

Enabled patients to communicate symptoms clearly

Allowed families to manage access without reducing patient autonomy

Reduced cognitive load by storing treatment plans and notes

“This app lets me describe my symptoms accurately and get the care I need.”

“I can delegate tasks to family members while still staying informed.”